Sir Vaughan Jones

The Fields Medal is often referred to as the Nobel Prize of mathematics. It is awarded only once every four years to up to four mathematicians worldwide, under the age of 40, for significant contributions to the study of mathematics.

When Vaughan was awarded the Fields Medal in 1990, it was specifically for the discovery of a new relationship within the realm he was studying: a new polynomial invariant for knots and links in 3-D space. It came as a surprise to many topologists who had been studying this field.

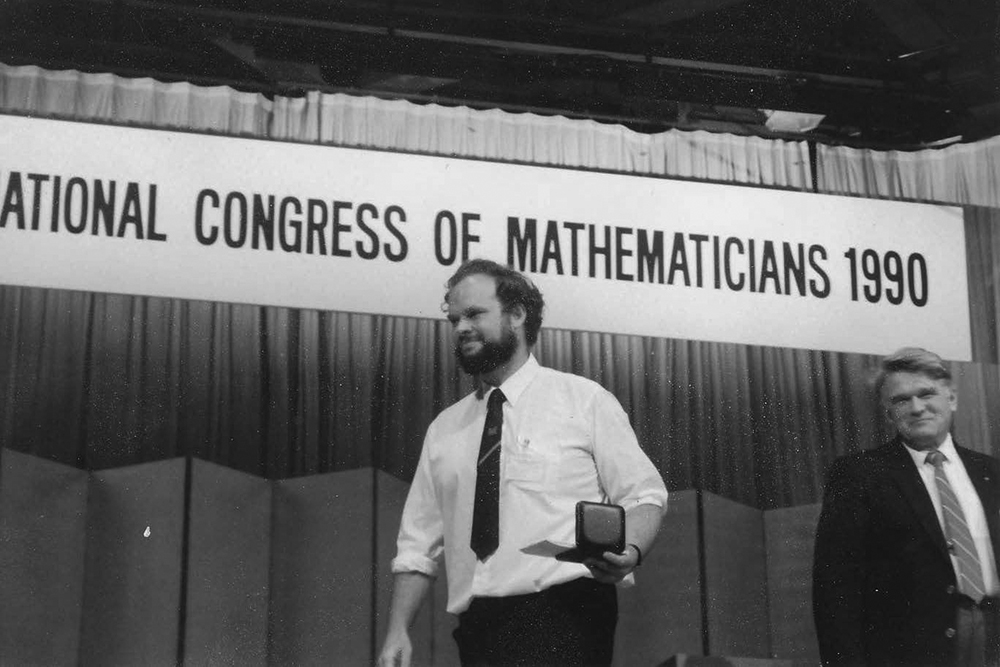

The only person from Aotearoa New Zealand ever to receive one is Sir Vaughan Jones, who received his Fields Medal in 1990 for work done on von Neumann Algebras and an unexpected application in a part of mathematics called topology. For many years, he was the only person in the Southern Hemisphere to have been awarded the Fields Medal. He accepted the Medal at the International Congress of Mathematicians in Kyoto, Japan. When he delivered his plenary lecture, he did so wearing an All Blacks rugby jersey.

Vaughan was born in Gisborne on 31 December 1952, and the family subsequently moved to Auckland. His parents divorced when he was young, so he went to boarding school at St Peter’s in Cambridge between the ages of 8 and 12. He then studied at Auckland Grammar School from 1966–1969. Vaughan credited both schools with giving him a strong foundation in music, sports, and academic studies. He won the Gillies Scholarship to study at the University of Auckland, studying a Bachelor of Science, graduating in 1972, and an MSc in 1973. He was awarded a Swiss Government scholarship to study for a Docteur ès Sciences (DSc – sometimes translated into PhD in English) at the University of Geneva. His thesis won the Vacheron Constantin Prize.

Vaughan moved to the United States in 1980, and taught at the University of California, Los Angeles, and the University of Pennsylvania before being appointed a Professor of Mathematics at the University of California, Berkeley. From 2011 he was the Stevenson Distinguished Professor of Mathematics at Vanderbilt University and remained Professor Emeritus at Berkeley. His work was in mathematical physics, Operator Algebras, and linked von Neumann Algebras and subfactors with Topology.

Topology is a branch of mathematics that describes mathematical spaces, and the properties that stem from a space’s shape. It is often called rubber sheet geometry. In topology shapes can be stretched, squished, or deformed, but in doing so, are not torn or merged. Two objects that can be deformed into the same shape are described as homeomorphic. Thus, a circle and a triangle in 2-D space are topologically identical, both enclosing one hole and so being equally complex; so too are a doughnut and a coffee cup in 3-D space.

Vaughan’s most well known work concerned knot theory, which is a discipline within topology that only deals with tori (the plural of torus – the doughnut shape) that cannot pass through themselves or others. More accurately, knot theory studies the Placement Problem: How one space can be embedded (placed) inside another space. In the case of knots, how one circle can be embedded inside the 3-D space. The problem of distinguishing such placements is very subtle and remarkably related to physics and natural science. Vaughan’s contributions to this field were fundamental and startling, changing the way we look at topology and its relationship with mathematics and with the natural world.

His discoveries allowed mathematicians to differentiate types of knots, and this had wider applications – for example, in biology, enabling scientists to see if two different types of RNA (genetic material) might be from the same source. His work led to the ‘Jones Polynomial’ and the solutions to several classical problems in knot theory. Vaughan’s work was abstract, but it had real significance in many other scientific fields, from quantum mechanics to quantum computers, biology, and many disciplines of maths and mathematical physics.

When Vaughan was awarded his medal in 1990, it was specifically for the discovery of a new relationship within the realm he was studying: a new polynomial invariant for knots and links in 3-D space. It came as a surprise to many topologists who had been studying this field. This is akin to a large group of prospectors working the same stretch of river when one of them strikes gold, although in his case the discovery was due to hard work and inspiration more than luck. Vaughan’s Fields Medal recognised him as an inventor of new mathematical machinery.

Vaughan typified the New Zealand spirit with his relaxed attitude and sense of collegiality. He was described as ‘informal’ and ‘encouraged the free and open exchange of ideas’ instead of a more hierarchical approach. He was also willing to share his ideas, and, in the best tradition of mathematicians, he often gave out details of what he was working on to allow others to contribute their thoughts, or to take those ideas further, rather than jealously guarding his own ideas to monopolise all the credit.

He was one of the principal founders, a director, and inaugural chairman of the New Zealand Mathematics Research Institute (NZMRI) from 1994–2020 and returned to New Zealand every year for 15 years to take an active part in the Institute’s summer school, to give back to the country he felt he had gained so much from.

Vaughan was appointed as a Distinguished Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit (DCNZM) in 2002, which was then redesignated to a Knight Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit (KNZM) in 2009. He was a member of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of London, awarded the Rutherford Medal and elected as an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of New Zealand Te Apārangi in 1991, and a Distinguished Alumnus Professor at his alma mater, the University of Auckland.

A keen choir singer, kite surfer and golfer, he often organised workshops in places where participants could go hiking or skiing. Scientific visits were often aligned with rugby tests, and he would always fit in a few rounds of golf on the way to his New Zealand-based workshops. At Berkeley he organised beer and pizza sessions for informal mathematical discussions after his Friday seminar, an institution he continued with at Vanderbilt. Over his career he supervised more than 30 doctoral students. He was a generous man and inspiring teacher.

Sir Vaughan Jones passed away in the USA in 2020, at the age of 67. He is survived by his wife Wendy (known professionally as Martha), their three children, and two grandchildren.

Explore the Legacy Project

.jpg)

Explore the Legacy Project

.jpg)

Explore the Legacy Project

.jpg)

.jpg)